Memory for Conversation

The amount of a conversation that can be accurately recalled in detail after a delay is limited. In on-going work in my lab, I am probing the limits on conversational memory, and the factors that predict what will be remembered. This work has important implications for theories of language use, and also has implications for the public sphere, including policy and law (Brown-Schmidt & Benjamin, 2017). After delays of several minutes to several weeks, participants can accurately recall a mere 0% to 40% of the total “idea units” expressed in the conversation, where an idea unit is defined as the smallest unit of language that has informational or affective value —typically a phrase or clause (e.g., Ross & Sicoly, 1979). Moreover, memory for conversation is asymmetric between partners, with better memory for what a person said in conversation, compared to what they heard (Fischer, et al., 2015; Yoon, et al., 2016; in press; McKinley, et al., 2017). For example, McKinley, et al., (2017) had partners complete a task in which they discussed a series of pictures. A subsequent recognition memory test indicated that the odds of correctly recognizing a picture was 2.64 times greater if the person had described it themselves, compared to when their partner described it to them. Yoon, et al. (2016) similarly shows that in a picture-description task, the person who described the picture is much more likely to later recognize it than the person who heard the description of it.

The fact that these memory asymmetries are observed in interactive conversational tasks (McKinley, et al 2017; Yoon, et al., 2016) shows that even if conversational partners accumulate information as part of common ground, this information is likely to be different due to basic memory asymmetries. In an on-going collaboration with Dr. Daphna Heller, we are examining the implications of these memory limitations and asymmetries for theories of communication, including the popular notion of common ground.

- Brown-Schmidt, S. & Benjamin, A.S. (2018). How we remember conversation: Implications in legal settings. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(2), 187-194.

- McKinley, G.L., Brown-Schmidt, S., & Benjamin, A.S. (2017). Memory for conversation and the development of common ground. Memory & Cognition, 45, 1281-1294.

- Yoon, S.O., Benjamin, A.S. & Brown-Schmidt, S. (accepted with minor revisions). Referential form and memory for the discourse history. Cognitive Science.

- Yoon, S. O., Benjamin, A. S., & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2016). The historical context in conversation: Lexical differentiation and memory for the discourse history. Cognition, 154, 102-117.

Language processing following brain injury

Over the last decade, Dr. Melissa Duff and I have together examined the impact of brain injury on conversational language use. Our work with persons who have bilateral hippocampal damage and severe memory impairment (amnesia) shows that both declarative and non-declarative memory systems support language processing in every-day settings (Duff & Brown-Schmidt, 2012). In some cases, we have observed remarkable independence of language processing from hippocampus, notably in the use of gesture to communicate common ground (Hilverman, et al. 2019), and in the activation of lexical semantics (Brown-Schmidt, et al., in press). Processing pronominal reference, as in "she", "he", or "they" often requires linking the pronoun to a person mentioned previously. We find notable impairment in this type of processing following hippocampal damage (Kurczek, et al. 2013) that repetition of the pronoun does not substantially alleviate (Covington, et al., 2020). In on-going work, we are examining the impact of traumatic brain injury as well as Alzheimer's disease on language processing in conversational settings and rich contexts. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIDCD R01 DC011755 and DC017926 to MCD and SBS).

- Brown-Schmidt, S., Cho, S.-J., Nozari, N., Duff, M. (in press). The limited role of hippocampal declarative memory in transient semantic activation during online language processing. Neuropsychologia.

- Covington, N, Kurczek, J. Duff, M.C., & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2020). The Effect of Repetition on Pronoun Resolution in Patients with Memory Impairment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 42(2), 171-184.

- Duff, M. C. & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2012). The hippocampus and the flexible use and processing of language. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 1-9.

- Hilverman, C., Brown-Schmidt, S., & Duff, M. C. (2019). Gesture height reflects common ground status even in patients with amnesia. Brain and Language, 190, 31-37.

- Kurczek, J., Brown-Schmidt, S., & Duff, M. (2013). Hippocampal contributions to language: Evidence of referential processing deficits in amnesia. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142, 1346-1354.

Perspective-taking and Language Processing

During conversation, interlocutors build upon the set of shared beliefs known as common ground. While there is general agreement that interlocutors maintain representations of common ground, there is little consensus regarding whether common ground representations constrain initial language interpretation processes (Brown-Schmidt & Heller, 2018). In my initial work, I examined the use of perspective information in the interpretation of informational questions during interactive conversation (Brown-Schmidt, Gunlogson, & Tanenhaus, 2008). We monitored participant’s eye movements as they engaged in an interactive dialog task during which they interpreted informational questions such as What’s above the cow with a hat? in scenes like the one below.

a-b: Example scenes (addressee’s perspective) from Brown-Schmidt, Gunlogson & Tanenhaus (2008), Experiment 2, replicated by Ryskin, Brown-Schmidt, Canseco-Gonzalez, Yiu & Nguyen (2014). Animals in white cubbyholes are in the common ground, animals in gray cubbyholes are in the addressee’s privileged ground. c: Target advantage scores over time when the competitor (horse with shoes) was in privileged ground (a), black line on graph (c); or in the common ground (b), red line on graph (c).

Questions typically ask about information not known to the speaker, thus if addressees are sensitive to the perspective of the speaker, they should be quicker to interpret the temporarily ambiguous question as asking about what was above the cow with the hat (as opposed to what’s above the cow with glasses) when the animal above the cow with glasses was already in common ground (b). The results showed that addressees use perspective to constrain interpretation of the question: following the temporarily ambiguous noun cow, addressees were more likely to look at the target (cow with hat and the animal above it) if the competitor was in common ground. The pattern of results was replicated when the competitor was brought into the common ground via. linguistic mention. An additional experiment conceptually replicated this finding in a completely unscripted conversational situation (Brown-Schmidt, et al., 2008; Experiment 1).

I proposed a Gradient-Representations theory of common ground (Brown-Schmidt, 2009; Brown-Schmidt, 2012; Brown-Schmidt & Fraundorf, 2015), in which I argue that the degree to which information is considered common ground varies in a gradient fashion. Evidence in support of this theory comes from findings that addressee commitment to discovering new information in a conversation increases the degree to which that information is considered common ground (Brown-Schmidt, 2012). Similarly, when common ground is established in interactive settings, common-ground based inferences are more likely, compared to non-interactive settings (Brown-Schmidt & Fraundorf, 2015; Brown-Schmidt, 2009). This work also shows that listeners integrate intonational contours of wh-questions with common ground during on-line processing. Whereas typical wh-questions are interpreted as asking for new information, this question=new inference is cancelled when produced with rising intonation (click for a typical example; and a rising example). In collaboration with my former student Dr. Rachel Ryskin, a large-scale study of individual differences in perspective-taking using similar measures, finds no relationship between eye-gaze measures of perspective-taking and individual differences in working memory or cognitive control (Ryskin, et al. 2015). This may be due to the fact that the gaze measures exhibited very low internal reliability – a problem that may be present for a variety of experimental approaches to cognitive processes.

- Brown-Schmidt, S., & Heller, D. (2018). Perspective taking during conversation. In: Oxford Handbook of Psycholinguistics, G. Gaskell & S.A. Rueschemeyer (Eds). Oxford University Press.

- Brown-Schmidt, S., Gunlogson, C. & Tanenhaus, M.K. (2008). Addressees distinguish shared from private information when interpreting questions during interactive conversation, Cognition, 107, 1122-1134.

- Brown-Schmidt, S. (2009). The role of executive function in perspective-taking during on-line language comprehension. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 893-900.

- Brown-Schmidt, S. (2012). Beyond common and privileged: Gradient representations of common ground in real-time language use. Language and Cognitive Processes, 27, 62-89.

- Ryskin, R.A., Brown-Schmidt, S., Canseco-Gonzalez, E., Yiu, E.K., & Nguyen, E.T. (2014). Visuospatial Perspective-taking in Conversation and the Role of Bilingual Experience. Journal of Memory and Language, 74, 46-76.

- Ryskin, R. A., Benjamin, A. S., Tullis, J., & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2015). Perspective-taking in comprehension, production, and memory: An individual differences approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(5), 898.

Multiparty Conversation

In a series of papers with former student Dr. Si On Yoon (Yoon et al., in press; Yoon & Brown-Schmidt, 2014; 2018; 2019a,b) we are pushing the boundaries of typical inquiry to examine language processing in multiparty conversation. Our research shows that speakers can maintain representations of joint knowledge shared with different individuals in three-party, four-party and even seven-party conversation. Speakers use distinct representations of the knowledge of multiple partners to design what they say in a way that is comprehensible to the current addressee or set of addressees.

- Yoon, S.O. & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2014). Adjusting conceptual pacts in three-party conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition.

- Yoon, S.O., & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2018). Aim Low: Mechanisms of audience design in multiparty conversation. Discourse Processes, 55(7), 566-592.

- Yoon, S.O. & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2019). Contextual integration in Multiparty Audience design. Cognitive Science, 43(12), e12807.

- Yoon, S.O. & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2019). Audience design in multiparty conversation. Cognitive Science, 43(8), e12774.

- Yoon, S.O., Benjamin, A.S. & Brown-Schmidt, S. (accepted with minor revisions). Referential form and memory for the discourse history. Cognitive Science.

Message planning and Utterance Formulation

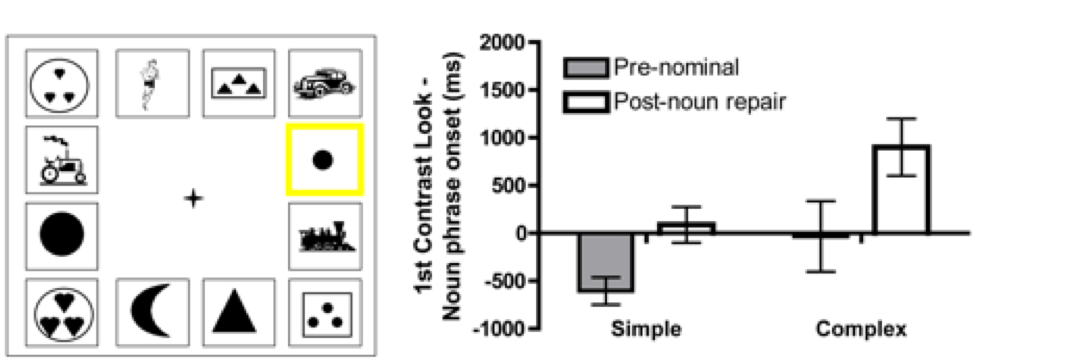

During unscripted speech, speakers coordinate the formulation of pre-linguistic messages with the linguistic processes that implement those messages into speech. In my initial work (Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2006), we examined the time-course of message planning by examining the planning of size terms in size-modified noun phrases. We used an interactive, unscripted conversational task in which pairs of naïve participants took turns telling each other to click on a highlighted picture (a) below as eye movements were monitored. In referential communication tasks, speakers typically use a size adjective only when they have noticed that there is another object in the scene that differs from the intended referent in size. In the current task, gaze is initially directed to the highlighted target object. Thus, the first gaze to the contrast object (in Figure a, the large circle) can be taken as an index of the time that the speaker first encoded the need to express size in her message.

In the first experiment, speakers referred to simple objects such as the small circle, or more complex objects, such as the circle with small hearts. The timing of the first look to the contrast object, relative to noun phrase onset (plotted in b) can give us insights into when size information was first planned, depending on utterance type. When pre-nominal modification was used (the small circle, or the circle with small hearts), first contrast fixation times were significantly earlier, relative to noun phrase (NP) onset, for the simple shapes compared to the complex shapes. This suggests that speakers planned the component of the message that encoded size information well before NP onset when the size term occurred early in the expression, but were able to delay planning of the size message when the size term occurred later in the expression. Similar delays in planning were observed for disfluent expressions (thee uh small peach, the peach, uh small one, Experiment 2), suggesting that speakers may use disfluency to incorporate late planned message elements into the ongoing expression. This interplay between referential form and message planning suggests a tight link between message planning and utterance formulation processes.

Dr. Agnieszka Konopka and I examined the process of constructing a contextually appropriate message and interfacing that message with utterance planning in English (the small butterfly) and Spanish (la mariposa pequeña) during an unscripted, interactive task. The coordination of gaze and speech during formulation of these messages was used to evaluate two hypotheses regarding the lower limit on the size of message planning units, namely whether messages are planned in units isomorphous to entire phrases or units isomorphous to single lexical items. Comparing the planning of fluent pre-nominal adjectives in English and post-nominal adjectives in Spanish showed that size information is added to the message later in Spanish than English, suggesting that speakers can prepare pre-linguistic messages in lexically-sized units. The results also suggest that the speaker can use disfluency to coordinate the transition from thought to speech.

Example scene from Brown-Schmidt & Konopka (2008).

References:

- Brown-Schimdt, S., & Tanenhaus, M.K. (2006). Watching the eyes when talking about size: An investigation of message formulation and utterance planning. Journal of Memory and Language, 54, 592-609.

- Brown-Schmidt, S., & Konopka, A. (2008). Little houses and casas pequeñas: message formulation and syntactic form in unscripted speech with speakers of English and Spanish. Cognition, 109, 274-280.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants No. 299 NSF BCS 10-19161, NSF BCS 12-57029, NSF BCS 15-56700, and NSF BCS 1921492. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation (NSF).